Come una collana di perle. Per Sabrina Mezzaqui

Non ho mai portato una collana. Ogni ornamento mi pesa, forse perché sento quello delle ossa che ci sono affidate. Un intero scheletro da sostenere. I miei anelli sono quelli della colonna vertebrale, i miei bracciali le giunture delle caviglie e dei polsi. Cerco le fondamenta, ciò che abbiamo di saldo, ciò che resta. È così sottile il filo che ci tiene uniti, che dà senso ai nostri gesti.

«Tutto questo universo è attraversato da me, come una collana di perle dal loro filo» (Bhagavad Gītā): leggo da una sequenza di frammenti che Sabrina Mezzaqui ha raccolto attorno al titolo Collana. Come nelle sue opere, in questo testo la voce dell’altro è accolta fino a fare emergere quella tessitura di cui è fatto il nostro stesso essere, intreccio di vite che ci precedono e ci attraversano, «inter-essere», come afferma Thích Nhất Hạnh in una pagina di cui Mezzaqui ha aperto i confini, mostrando delicatamente l’intelaiatura che la sostiene.

Sono stata a trovarla a Marzabotto. Dalla piccola stazione abbiamo raggiunto in pochi passi il suo appartamento, siamo uscite a camminare fino alla necropoli etrusca, poi attraversando il paese siamo entrate nel Sacrario, e infine nel suo laboratorio. Sono venuta contenendo il vuoto di una perdita. Il filo spezzato. Tutte le perline che componevano la mia vita, disperse a terra. In ginocchio sul pavimento cerco di raccoglierle mentre rimbalzano e rotolano ancora più lontano.

I versi di Salva con nome di Antonella Anedda mi hanno condotto qui. Alcune frasi della sezione Cucire sono state infatti riscritte da Sabrina Mezzaqui con la propria grafia e ricamate su un quaderno di stoffa. Scrivere una parola con ago e filo significa farla passare attraverso il proprio corpo e viverla punto per punto.

È un’opera di dedizione in cui si riversa tutto l’amore e la costanza che servono per portare alla luce. Contenendo una parola nei propri gesti, facendosene tramite, si apre nel proprio corpo uno spazio a cui non arriva la mente con la sua comprensione. È questo probabilmente il significato di trascrivere, dare le proprie mani alla voce di un altro, come in un atto di affidamento, in una preghiera. Le opere di Sabrina Mezzaqui come i versi di Antonella Anedda, provengono da quella pratica di attenzione che nasce per affrontare la perdita; sono un esercizio di ascolto per accogliere il vuoto e trasformarlo.

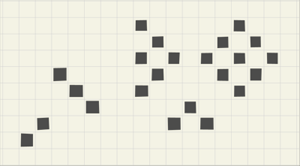

Nell’appartamento di Marzabotto, su un piccolo leggio di legno addossato alla parete, sta un dizionario aperto. Poco più in alto, due finestre incorniciano sagome di case e di alberi. Riconosco le immagini di Quando le parole atterrano, dove Mezzaqui legge le tessere della luce che attraversa le persiane, il racconto della pioggia sui vetri. C’è qualcosa di profondamente arcaico in questo sguardo capace di riconoscere nella realtà la traccia di una scrittura, di sentire la materia della parola come quella del reale, plasmate da una stessa energia, da uno stesso senso che chiama. Così in una sua opera del 2006, Segni, dove un libro si apre generando. Dalle sue pagine bianche si innalzano sagome nere di uccelli in volo, liberandosi nello spazio. È lo stesso miracolo a cui assistiamo in una delle sequenze centrali di un film di Tarkovskij, Nostalghia, dove uno stormo di uccelli fuoriesce vociante dal grembo della Vergine. Anche questo libro aperto che ci mostra Mezzaqui è il luogo sacro dell’origine. Dalle sue pagine sorge la vita, il suo significato che si dona, che sta a noi decifrare. Ma quello stesso volo può leggersi anche nel verso opposto: sono gli uccelli a posarsi sulla pagina, depositando la loro verità. È la natura stessa che scrive attraverso le sue forme, moti e ritmi, facendo affiorare "segni" per il nostro cammino.

Qualcosa di simile a un’obbedienza governa l’arte di Sabrina Mezzaqui, un’armonia ancestrale, una giustizia che ogni gesto è chiamato a ristabilire. Siamo ricondotti a quella circolarità che apparteneva alla civiltà contadina: lo sgusciare lento di semi come grani di un rosario, il fare quotidiano e liturgico di una comunità operosa. Molte delle opere di Mezzaqui sono nate così, dentro il cerchio paziente di mani che hanno condiviso il lavoro; minimi gesti ripetuti, in una dedizione che ha reso possibile attraversare il tempo, restituendo qualcosa che è fatto della sua stessa sostanza. Che sia carta o stoffa, parola scritta o immagine video, è infatti sempre il tempo condensato la materia delle sue opere: lentamente rilasciano la propria energia, i gesti e la vita di cui sono composte. Non è possibile rimanere spettatori passivi: come di fronte a una poesia, la carica di significato di cui siamo investiti chiama a metterci a nostra volta all’opera, a dipanare, ad accogliere nelle nostre mani, a custodire. La sua arte è così umile e radicale nel porsi come gesto anonimo, originario, che arriva quasi a confondersi con il lavorio che gli agenti atmosferici attuano sulle cose. La sensazione è spesso quella di trovarsi di fronte all’opera paziente e metodica di un formicaio, di un’arnia, come se Mezzaqui si fosse sintonizzata con il movimento stesso presente nella natura, con i suoi cicli di distruzione e ricomposizione. Diversi suoi lavori sono metamorfosi attraverso cui un libro viene liberato dalla propria forma per essere restituito a un significato che sta oltre le parole, nella materia stessa della lingua, in quel fare (poiein) che è all’origine di ogni creazione di senso.

Appartiene all’arte di Mezzaqui il tempo dell’incanto, quella dimensione sospesa in cui, come nelle fiabe, avvengono i passaggi di stato, le trasformazioni. Siamo riportati a quella forza primigenia che sorregge e moltiplica il gesto di un singolo in quello della comunità che lo precede, che può essergli accanto. Come rispondendo a uno degli appelli che Mezzaqui lancia per portare a compimento le sue opere, siamo chiamati a entrare insieme in questo tempo altro, ritrovare il filo, perlina dopo perlina, creare la nostra collana. Seduti a un tavolo, al lavoro, come stando in ginocchio. Tenendo questo istante nelle mani, adesso.

Sabrina Mezzaqui

(Ottobre 2017)

—Franca Mancinelli

Like a Pearl Necklace. For Sabrina Mezzaqui.

I have never worn a necklace. Any ornament weighs down on me, perhaps because I sense the one made of the bones entrusted to us. A whole skeleton to support. My rings are those of the spine, my bracelets the joints of the ankles and the wrists. I seek the foundations, what is solid in us, what remains. The thread that holds us together, that gives meaning to our gestures, is so thin.

"I go through this whole universe as does a thread its pearl necklace" (Bhagavad Gītā): I am reading from a sequence of fragments that Sabrina Mezzaqui has collected around the title Necklace. As in her artworks, in this sequence the voice of the other is incorporated until emerges the weave of our being, the interwoven lives that go before and through us, our "interbeing" as Thích Nhất Hạnh calls it on a page whose margins Mezzaqui has opened, delicately showing the framework that supports it.

I have gone to see her in Marzabotto. From the small station we reached her apartment in a few footsteps, went out to walk all the way to the Etruscan necropolis, then, crossing the town, entered the Sanctuary and, finally, her workshop. I have come with the void of a loss inside me. The broken thread. All the beads that strung my life together have been scattered on the ground. Kneeling on the floor, I try to pick them up as they bounce and roll away even further.

The poems of Antonella Anedda’s Save As have brought me here. Some sentences from the “Sewing” section have in fact been copied out by Sabrina Mezzaqui in her own hand and embroidered on a cloth notebook. Writing a word with a needle and thread means putting it through your body and experiencing it pinprick by pinprick. It is a work of dedication into which all the love and perseverance needed to bring something to light is poured. By keeping a word in your gestures, by acting as its go-between, a space opens up in your body that the mind cannot reach with its understanding. This is probably what transcribing means—giving one’s hands to another person’s voice, as in an act of trust, as in a prayer. Sabrina Mezzaqui’s artworks, like Antonella Anedda’s poems, come from a practice of attention born to face loss; they are exercises in listening to embrace the void and transform it.

In Marzabotto’s apartment, on a small wooden lectern leaning against the wall, there is an open dictionary. A little higher, two windows frame silhouettes of houses and trees. I recognize the images of When Words Land, in which Mezzaqui reads slits of light shining through the shutters, the story of rain on the pane of glass. There is something profoundly archaic in her gaze, capable of recognizing the traces of writing in reality, of feeling the matter of words as something real, shaped by the same energy, by the same meaning that beckons. So it is in one of her works from 2006, Signs, in which a book opens, giving birth. From its white pages rise black silhouettes of flying birds, freeing themselves into space. It is the same miracle that we witness in one of the central sequences of Tarkovsky’s film Nostalghia, where a flock of clamoring birds emerges from the Virgin’s womb. This open book that Mezzaqui shows us is also the sacred place of the origin. From its pages, life surges forth, its meaning which is given to us, which is up to us to decipher. But that same flight can also be read in the opposite direction: it is the birds that alight on the page, laying down their truth. It is Nature itself that writes through its forms, motions, and rhythms, making "signs" emerge along our path.

Sabrina Mezzaqui’s art is governed by something similar to obedience, an ancestral harmony, a kind of justice that every gesture is called upon to restore. We are led back to that circularity characteristic of peasant civilizations: the slow shelling of seeds like the grains of a rosary, the liturgical daily doings of an industrious community. Many of Mezzaqui’s works have been born in this way, within the patient circle of hands that have shared the work; minute repeated gestures, with a dedication that has made it possible to go across time, giving back something that has been fashioned of its own substance. Whether paper or cloth, written words or a video image, time is always the condensed matter of her works: they slowly release their energy, the gestures and the life of which they consist. It is impossible to remain passive spectators: as with a poem, the charge of meaning with which we are invested beckons us to get to work in turn, to disentangle, to gather into our hands, to care for. Her art is so humble and radical in its anonymous, original gestures that it almost blends with the effects that atmospheric agents have on things. The sensation is often that of facing the patient, methodical work of an anthill, a beehive, as if Mezzaqui were attune to the movement itself present in nature, with its cycles of destruction and re-composition. Several of her works are metamorphoses through which a book is freed from its form and returned to a meaning that lies beyond words, in the very matter of language, in that making (poiein) at the origin of any creation of meaning.

To Mezzaqui’s art belongs the time of enchantment, that suspended dimension in which, as in fairy tales, transformations and changes of state occur. We are brought back to the primordial force that supports and multiplies an individual’s gesture into that of the community which precedes him, which can be close to him. As if responding to one of her “calls” that she makes to carry out her works, we are beckoned to enter this other time together, to find the thread, bead after bead, to create our necklace. Sitting at a table, at work, as if kneeling. Holding this instant in our hands, from now on.

Like a Pearl Necklace. For Sabrina Mezzaqui.

I have never worn a necklace. Any ornament weighs down on me, perhaps because I sense the one made of the bones entrusted to us. A whole skeleton to support. My rings are those of the spine, my bracelets the joints of the ankles and the wrists. I seek the foundations, what is solid in us, what remains. The thread that holds us together, that gives meaning to our gestures, is so thin.

"I go through this whole universe as does a thread its pearl necklace" (Bhagavad Gītā): I am reading from a sequence of fragments that Sabrina Mezzaqui has collected around the title Necklace. As in her artworks, in this sequence the voice of the other is incorporated until emerges the weave of our being, the interwoven lives that go before and through us, our "interbeing" as Thích Nhất Hạnh calls it on a page whose margins Mezzaqui has opened, delicately showing the framework that supports it.

I have gone to see her in Marzabotto. From the small station we reached her apartment in a few footsteps, went out to walk all the way to the Etruscan necropolis, then, crossing the town, entered the Sanctuary and, finally, her workshop. I have come with the void of a loss inside me. The broken thread. All the beads that strung my life together have been scattered on the ground. Kneeling on the floor, I try to pick them up as they bounce and roll away even further.

The poems of Antonella Anedda’s Save As have brought me here. Some sentences from the “Sewing” section have in fact been copied out by Sabrina Mezzaqui in her own hand and embroidered on a cloth notebook. Writing a word with a needle and thread means putting it through your body and experiencing it pinprick by pinprick. It is a work of dedication into which all the love and perseverance needed to bring something to light is poured. By keeping a word in your gestures, by acting as its go-between, a space opens up in your body that the mind cannot reach with its understanding. This is probably what transcribing means—giving one’s hands to another person’s voice, as in an act of trust, as in a prayer. Sabrina Mezzaqui’s artworks, like Antonella Anedda’s poems, come from a practice of attention born to face loss; they are exercises in listening to embrace the void and transform it.

In Marzabotto’s apartment, on a small wooden lectern leaning against the wall, there is an open dictionary. A little higher, two windows frame silhouettes of houses and trees. I recognize the images of When Words Land, in which Mezzaqui reads slits of light shining through the shutters, the story of rain on the pane of glass. There is something profoundly archaic in her gaze, capable of recognizing the traces of writing in reality, of feeling the matter of words as something real, shaped by the same energy, by the same meaning that beckons. So it is in one of her works from 2006, Signs, in which a book opens, giving birth. From its white pages rise black silhouettes of flying birds, freeing themselves into space. It is the same miracle that we witness in one of the central sequences of Tarkovsky’s film Nostalghia, where a flock of clamoring birds emerges from the Virgin’s womb. This open book that Mezzaqui shows us is also the sacred place of the origin. From its pages, life surges forth, its meaning which is given to us, which is up to us to decipher. But that same flight can also be read in the opposite direction: it is the birds that alight on the page, laying down their truth. It is Nature itself that writes through its forms, motions, and rhythms, making "signs" emerge along our path.

Sabrina Mezzaqui’s art is governed by something similar to obedience, an ancestral harmony, a kind of justice that every gesture is called upon to restore. We are led back to that circularity characteristic of peasant civilizations: the slow shelling of seeds like the grains of a rosary, the liturgical daily doings of an industrious community. Many of Mezzaqui’s works have been born in this way, within the patient circle of hands that have shared the work; minute repeated gestures, with a dedication that has made it possible to go across time, giving back something that has been fashioned of its own substance. Whether paper or cloth, written words or a video image, time is always the condensed matter of her works: they slowly release their energy, the gestures and the life of which they consist. It is impossible to remain passive spectators: as with a poem, the charge of meaning with which we are invested beckons us to get to work in turn, to disentangle, to gather into our hands, to care for. Her art is so humble and radical in its anonymous, original gestures that it almost blends with the effects that atmospheric agents have on things. The sensation is often that of facing the patient, methodical work of an anthill, a beehive, as if Mezzaqui were attune to the movement itself present in nature, with its cycles of destruction and re-composition. Several of her works are metamorphoses through which a book is freed from its form and returned to a meaning that lies beyond words, in the very matter of language, in that making (poiein) at the origin of any creation of meaning.

To Mezzaqui’s art belongs the time of enchantment, that suspended dimension in which, as in fairy tales, transformations and changes of state occur. We are brought back to the primordial force that supports and multiplies an individual’s gesture into that of the community which precedes him, which can be close to him. As if responding to one of her “calls” that she makes to carry out her works, we are beckoned to enter this other time together, to find the thread, bead after bead, to create our necklace. Sitting at a table, at work, as if kneeling. Holding this instant in our hands, from now on.

(October 2017)

—Franca Mancinelli

—translated from the Italian by John Taylor

—translated from the Italian by John Taylor